Overcoming our own limitations using the Monte Carlo method

One of the most common and frustrating questions to answer in any creative endeavour is: “When will it be done?”.

The first thought that should pop into any rational person’s head on hearing this is probably, “How the hell should I know?”.

However, for some reason our evolution has left us predisposed to thinking we can easily give a correct answer.

So now we umm and aah and eventually give some pronouncement which, if delivered with enough certainty, suddenly, and to our bewilderment, becomes a binding oath that we’re expected to fulfil.

Why Humans are Awful...at Esimating

It turns out that all of us are empirically terrible at estimating.

First up, there’s what’s referred to as the planning fallacy. This is where our attention on the task we’re being asked about overrides our ability to take into account historical facts that might be relevant. By focusing solely on estimating what's in front of us we become myopic about the context: we fail to take into account complications that might arise along the way.

You’re probably thinking, “Ok, so that’s not great but we can probably account for those things.” And you’re right ... except there’s one other issue: our hardwired optimism bias.

It turns out that for (possibly) evolutionary reasons we underestimate how difficult a given task will be. We also underestimate how likely it will be that we will run into any issues along the way. This is best summarised in Hofstadter's law:

It always takes longer than you expect even when you take into account Hofstadter’s law.

Adding a Buffer

We know we’re bad at estimating we know we're overly optimistic and we know Hofstadter’s law. So for any estimate surely we just add 20%, 30%, 75%? That would give us an answer. That’s at least more accurate right?

Well, there’s also another problem here. Opportunity cost.Let’s use an example. Imagine a builder quoting for work and, knowing how bad they are at estimating, adding on 75% to cover themselves. The estimate may indeed cover them but if they have a competitor who is able to estimate more accurately then, all else being equal and the customer caring mainly about price, they will only end up with those jobs that their overestimate is in fact and underestimate for. That way lies bankruptcy.

Maybe There is a Better Way

So the problem is we know what we have to account for but we need to find some way of doing it more accurately.

So what if we changed our perspective and asked if we or anyone else had faced something similar in the past? What if we could compare it to multiple things that either we or others had done in the past that were equivalent? Maybe this might deal with our inherent fallibility. But, we should also be honest about the assumption we're making:

- We expect the future to look like the past

Our Scenario

For the rest of this article we’ll assume we’re an aspiring author that’s just received their first book deal. Amazing! Go us!

The deal itself is to write a book of 35,000 words and our publisher needs to know when we’ll have the first draft finished so that he can edit, market, publish and ultimately make a profit from our work. Can we tell him when it’ll be ready on day one?

Yes, but it will be wrong.

As an aspiring author we have absolutely no way of knowing how fast we’ll be able to write anything and we especially don’t know what issues will come up along the way. So cleverly we ask our publisher to give us two weeks and we’ll come back with a more accurate answer.

A Naive Approach

After two weeks we have collected some data on our progress for words written for each day shown in the array below.

// The length of our book in words

const bookLength = 35000

// The data we have collected on the speed at which we write.

// We tend to write nothing at weekends and on the odd day while editing acutally

// delete some of our work

const wordsPerDay = [126, 470, 350, 750, 200, 0, 0, -100, 25, 55, 504, 0, 0, 0]

A naive but at least data based approach at this point would be to take the average number of words we’ve written per day and use that to divide the number of words to write giving us the number of days until we finish.

const averageRate = wordsPerDay.reduce((a,b) => a + b, 0) / wordsPerDay.length

const howLong = Math.round(bookLength / averageRate)

// => 206

This is a great start but there’s a slight problem. We’ve gone from being completely wrong to being precisely wrong.

Improving our Process

The key is that by averaging out the pace at which we write we’ve just removed the variance that we know is critical to understanding how we'll perform over time.

So now we do away with the idea that we can give a precise answer. We accept that we have no way of knowing the future. Instead we focus on being imprecisely right rather than precisely wrong.

Building the Model

So what does this look like? To start with we try and work out one plausible estimate based on our historical data. Then we do the same thing again and again multiple times until we have a mass of results. If we then sort these into ascending order we’ll see that we have a distribution of plausible estimates. And it is this range of estimates that can give us our answer.

Take a look at the code below which illustrates each step of this

const runSimulation = (

data,

bookLength,

numberOfSimulations,

result =[]

) => {

// if there are no more simulations left, give us the results

if(numberOfSimulations === 0) return result

// pick a random number between a high and a low

const sample = (distLow, distHigh) =>

Math.floor(Math.random() * (distHigh - distLow + 1) + distLow)

// get the highest and lowest value from our data

const {

0: distLow,

[data.length - 1]: distHigh

} = [...data].sort((a,b) => a - b)

// randomly pick how many words we write in a day

// minus that number from the number of words left to write

// add one to the number of days and repeat until we have no words left to write

// at the end tell us how many days we took

const days = (bookLengthRemaining, howLong = 0) => {

if(bookLengthRemaining <= 0) return howLong

return days(

bookLengthRemaining - sample(distLow, distHigh),

howLong + 1

)

}

// add the number of days it took to our results

// reduce the number of simulations left by one

// run again until no simulations are left to run

return runSimulation(

data,

bookLength,

numberOfSimulations - 1,

[...result, days(bookLength)]

)

}

// actually run our simulations 10 time and sort the results

runSimulation(wordsPerDay, bookLength, 10).sort((a,b) => a - b)

// => [101, 102, 102, 104, 104, 108, 110, 112, 117, 129]

What we've just used is the Monte Carlo method which excels in cases where you have a range of possibilities or risks. Interestingly, it was first used to understand the risks and stakes in various gambling games hence the name.

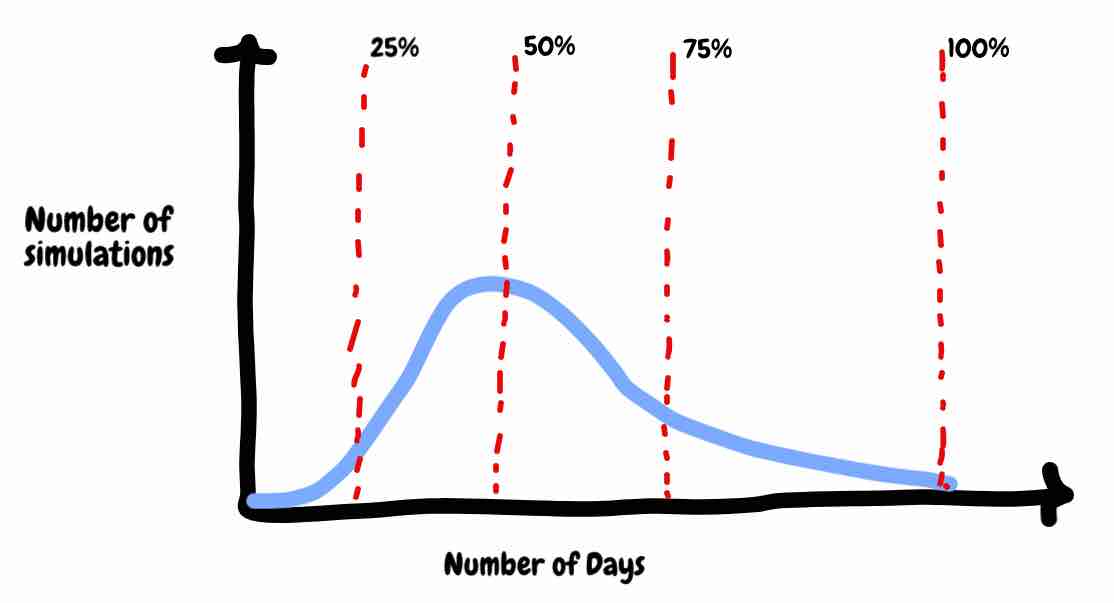

But enough about that. We have a model and we've run ten simulations each of which has given us a plausible result. If you plotted these onto a graph it would likely end up looking something like this:

Thinking about what this represents. If we take our first result this would indicate a perfect future. Every morning we woke to sunshine and the sound of birds, ideas flowed straight from the universe through the keyboard and into the written word at a phenomenal pace and we were able to complete the book in record time.

At the other end, our last result would indicate a future where we were constantly afflicted both with disease and writers block.

However, most of our scenarios represent a mixture of good days and bad days bounded by our past performance.

So how is this useful to us?

Well if instead of running this ten times you ran it ten thousand times you might be interested in knowing the 85% of eventualities finished within a certain timeframe. Would you be happy with an 85% chance? If not you could always see when 90% or even 100% of your scenarios had finished.

Forecasts not Estimates

When will it be done? We now have an answer. Is it perfect? Absolutely not but we’re not looking for perfection. In fact, we're looking for something that's a little bit more like a weather forecase.

How much do you trust the weather forecast to be accurate 30 days out?

It’s usually just a good indication but you wouldn’t trust it to make any important decisions.

What about a weather forecast for the day ahead?

I'd say that it’s usually pretty accurate.

When it comes to the question of when things will be done we’d like to take the same approach. And the best thing for us is that we know that our forecast will improve over time.

Improving with Time

At the beginning of this journey we had no idea how fast we could write. Now, after the first two of weeks we've managed to collect some data and we have some idea of when we might be done. However, as with all models, your result is only as good as your input. We shouldn't trust our forecasts too much right now and we should be prepared for some change.

After one month we will have a good understanding of our pace of writing will also know that we are able to write at a more consistent pace. We have also had a few days where we were dealing with an emergency and couldn’t write anything. Our model now takes this into account.

After some months we have experienced a few hiccups but maintained a consistent pace. In fact you can actually see that over time we have begun to improve. To take this into account we could change the range we pick from over time or given enough data we could simply sample from our data rather than pick from a range. At this point we're beginning to optimise our model to take into account the specifics of our acutal case. It's at this point that you would be pretty happy with the outputs you are generating to the point where you could commit to delivering your book by a given time. Perhaps most valuably, if everything works out well you now have a great way of understanding how long it might take you to write the sequel.

What Should I Take from All of This

If there's one thing that you take away from this article it should be this. Be incredibly skeptical of anything that involves human estimation. Always question its validity. Be especially skeptical of processes that wrap human estimation in statistics. It's the equivalent of putting makeup on a pig and the results are if anything more useless because of all the time spent wrapping them up.

So if you are ever in a position where you're being asked: "When will it be done?" You can always do much worse than reaching into your toolbox and pulling out a bit of Monte Carlo.